ONE

Next to torture, art persuades most

George Bernard Shaw

The British novelist, Mary Ann Evans, who wrote during the last century under the name George Eliot, believed that her work could effect change. "My function is that of the aesthetic teacher;" she said," the rousing of the nobler emotions, which make mankind desire the social right." And she was right: within living memory there have been moments in history when artists, crafts-persons and designers actually participated directly in the evolution of their culture; moments in which they called on everyone to change their lives in fundamental ways and the public responded; Malevich and Speer are examples, and it was George Bernard Shaw who once said: “Next to torture, art persuades most.” Shaw’s sloganeering makes a crucial distinction between kinds of power; on the one hand, torture is designed to force submission, while on the other there are the more gentle powers of persuasion. Mary Ann Evans’ ambitions, and for that matter most of the creative disciplines, were aligned with Joseph Nye’s notion of soft power. “Soft power,” Nye tells us, “is the ability to get what you want by attracting and persuading others to adopt your goals. It differs from hard power, the ability to use the carrots and sticks of economic and military might to make others follow your will.” It certainly remains difficult to say that creative disciplines which attempt to project hard power using avenues of confrontation continue to have much leverage within our culture. These days, when the creative disciplines claim reform by confronting power, in reality, their position is more like having permission to rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic.

But by exercising hard power or even soft, the creative disciplines seem out of position to serve as the agency for reform. We are not capable of more than picturing the prospect of reform - never the instrument for its creation. In the wake of this reasoning it is easy to understand that when Barbara Kruger's picture says: "We Are Not What We Seem" it takes on an ironic double meaning. It is the voice of the feminine "WE" who proclaim that women are more than what culture has made them appear; that they possess a depth otherwise unrecognized by a culture fierce with discrimination. But at the same time this voice is the "WE" of artists, crafts-persons and designers who must frankly admit that we are not at all what we seem. The power of social and political reform is a power we are largely helpless to enact.

Cornel West rightfully laments the way the creative disciplines condemn themselves to manufacturing transgression against power by consistently constructing alternatives as an escalation of radicality rather than by inventing new forms. He is right to deplore our tail chasing. If artists, crafts-persons and designers want to participate in reshaping their political, social, economic and cultural future they will have to begin to think beyond augmenting the existing forms of power, beyond the stylistic tradition of making their creations politically explicit, or belligerent. History tells us how empty this form of radicalism actually is, how sadly self serving it has become.

These days, the conventional styles of the counterculture shadow box with politics. These prevailing “political-styles” detain us from effecting fundamental and equitable changes within our society. They rehearse the model of engagement. They pretend to engage political or social systems and in turn, power pretends the art, craft and design have some unspecified but benevolent effect, by not censoring it. Where is the difference between this and James Baldwin’s description of black domestics in white homes stealing money that the whites expected them to take because it served to reinforce the white’s superiority and the black’s degradation? Sanctioned modes of art, craft and design claiming to inspire or enact social or political reform have lost their tooth and exist like a service industry providing an otherwise oppressive system with the sterling centerpiece of its own benevolence, tolerance and altruism.

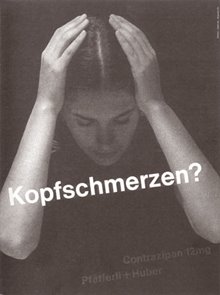

And so, on the rare occasion when the creative disciplines may legitimately make claim to speaking truth to power - with the result of making way for reform using their creativity as the instrument of social consciousness - it is always an occasion for recognition and self-congratulations. Such was the case of the Swiss graphic designer Ernst Bettler, a protagonist in history who, through his work, provoked real and measurable social change. Adbusters called his work "one of the best design interventions on record.” But before Christopher Wilson published an article on Bettler in the second issue of Dot Dot Dot, a magazine of visual culture, the designer was virtually unknown. The article titled “I’m Only a Designer; The Double Life of Ernst Bettler,” recounts how in late 1958 Bettler was commissioned to design advertisements for the Swiss pharmaceutical manufacturer Pfäfferli+Huber. Though Bettler knew that Pfäfferli+Huber had collaborated with the Nazis, carrying out medical experiments in concentration camps, he accepted the commission intent on subversively damaging the company’s reputation. He created four posters to celebrate Pfäfferli+Huber’s fiftieth anniversary, each an exemplary example of the International Typographic Style. Each poster features an ordinary person, an older man, two children, and a woman. In the poster with the woman, advertising Pfäfferli+Huber’s pain reliever “Contrazipan,” she is seen holding her head in both hands with the question “Kopfschmerzen?” (headache) set at a slight angle crossing her arms. The placement of the word loosely creates the letter “A” when seen in relation to the woman’s arms.

Bettler used the other three posters to create vaguely abstract versions of the letters “N,” “Z,” and “I” so that when the four posters were seen together in hundreds of locations around the Swiss city of Burgwald, and neighboring Sumisdorf, they spelled out the word NAZI. Once reminded of Pfäfferli+Huber’s infamous collaboration, public outrage followed, and with a matter of weeks the pharmaceutical manufacturer was ruined. It is a story as rare as it is extraordinary, a story of a creative discipline using soft power with effect to change the course of culture. It is a story that historians and critics of graphic design have acclaimed time, and again. Creativepro.com described Bettler’s posters as “brilliantly subversive work,” while Phaidon published Michael Johnson’s Problem Solved, where Bettler is paid tribute as one of the "founding fathers of the 'culture-jamming' form of protest."

Bettler’s story, a defining moment in design’s modest history of enacting real and measureable change, would be an inspiration to us all, had any of it been true. It was a hoax; there is no designer named Bettler, no Pfäfferli+Huber, no posters and no Swiss cities named Burgwald, or Sumisdorf. Two years after the Wilson article was published Andy Crewdson revealed it as a fraud. Given design’s historical lack of any creditability at creating substantive and measurable change, shouldn’t the Bettler story have instantly appeared, at best, incredible if not an outlandish fairy tale? And what does it tell us that the creative disciplines so easily accepted Bettler’s story at face value? Perhaps it reveals the extent of the lack of historical knowledge and critical reflection on hand in the design world. Moreover it begs the conclusion that there is a near total lack of the understanding of, and ability to conduct basic research within the discipline. Writing for eyemagazine.com after Bettler had been unveiled as a ruse, Rick Poynor commented: “It reveals how skimpy standards of research, validation and basic knowledge can be in design book publishing.” Not to mention in the practice of design. Exhibit A? Michael Bierut’s disturbing account, titled “Designing Under the Influence,” of the historical amnesia that has by now become commonplace both at the university and in professional life.

Wouldn’t the powerlessness to critically reflect upon historical precedents make it more than likely that - like Bierut’s young designer – there will be a good deal of re-invention going on? Or more disturbing, does all of this, from Bierut’s young designer to the Bettler hoax, tell us that there is such a broad and deep acceptance of the ineffectualness of the creative disciplines to provoke real social change that our fanatical desire for it to be otherwise only further blinds us to the reality of our own historical legacy? Would we believe anything to make it true that art, craft and design had some measurable effect? And what must this say about research through practice, still nascent and under development? Given an apparent dearth of the historical knowledge that would spark critical reflection and research in the creative disciplines, how shall we regard research through practice? Is research through practice merely a form of affirmative action aimed towards the creative disciplines? Is it more than a diminutive version of research, granted from the belief that broad values may be gained from diversity in the field of research, by giving underrepresented minority groups in this field (artists, designers and crafts-persons) a significantly greater chance of doing some form of research however Lilliputian?

Doesn’t this raise the question of whether there should be a difference made between research in the humanities and research through practice in the arts? Is research through practice simply a matter of preferential treatment bestowed out of empathy for our helplessness at historical and critical reflection? Is it just another form of the innocent eye test?

TWO

This studio will use case studies from the creative disciplines, research through practice and research as tools to generate a body of work, and discussion about, and critical reflection upon, deception, research through practice and research in general and the distinction between those.

We will take a field trip to the Armémuséet in Stockholm, after which students will be divided into interdisciplinary teams and given a theme around which they are to develop a studio project which will support arguments for or against a distinction between research through practice and research, or as evidence of a third or hybrid methodology between the two.

Keywords: communication, deceptive art (design and craft), soft power, performative aspects of research, history, critical reflection.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

The Innocent Eye Test, Painting by Mark Tansey, 1981

Josef Müller-Brockmann, 1960

Ernst Bettler, 1959

Research Through Practice, Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, Fall 2008 Jenny Bergström and Ronald Jones

The Innocent Eye Test, Painting by Mark Tansey, 1981

Josef Müller-Brockmann, 1960

Ernst Bettler, 1959

Links

List of readings

- "I'm only a designer": The double life of Ernst Bettler, Christopher Wilson

- A Physicist Experiments With Cultural Studies, Alan D. Sokal

- Anti-Americanism: America must regain its soft power, Joseph S. Nye

- Design Thinking, Tim Brown

- Designing Under the Influence, Michael Bierut

- Does Interdisciplinarity really exist? Peter Weingart and Nico Stehr

- Fail Again. Fail Better. Ronald Jones

- Interdisciplinarity in a Disciplinary Universe: A Review of Key Issues, Kathryn Shailer

- Learning from Experience: approaches to the experiential component of practice-based research, Michael A R Biggs

- Research in Art and Design, Christopher Frayling

- She Says It's True, Her Memoir of Forging, Julie Bosman

- The "Ernst Bettler" problem, Rick Poynor

- The Debate on Research in the Arts, Henk Borgdorff

- The Power of Persuasion, Michael Schrage

- The Sokal Hoax, Alex Boese

- Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity, Alan D. Sokal

- Welcome to the Experience Economy, B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore

- Will the Real Ernst Bettler Please Stand Up? Michael Bierut